Week 3: Lexeme formation II

English Morphology

2024-11-05

Today we are taking an excursus

- So far we have seen how English creates new lexemes

- The question is: what about other languages?

- What other languages do you speak?

- Can you think of other ways to create lexemes that can’t be found in English?

Morphological analysis

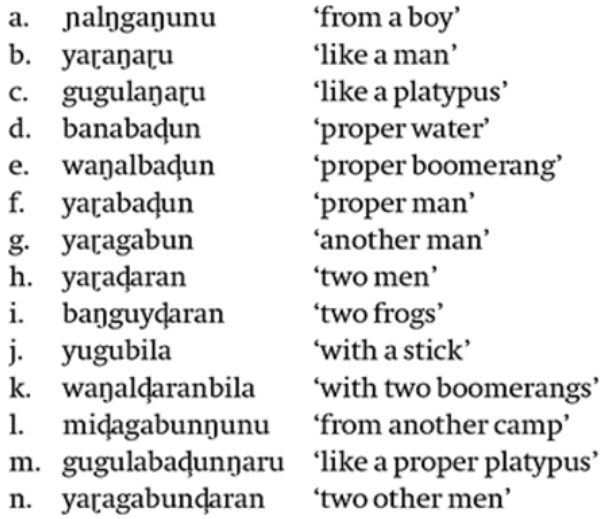

- Can you analyze the words from this language? (Dyirbal)

What does this exercise tell us about morphology?

- Not all languages are the same: some prefer using prepositions, etc. while others form new lexemes

- When running into different languages, knowing only what works for our language may lead us to the wrong conclusions

Trust me, I’m a linguist!

You might have heard the claim that tHe EsKimO hAvE 50/100/150/\((\sqrt -1) x 5!\) wOrDs FoR sNoW , but at this point you should be able to tell that things are not that simple. Any thoughts?

Infixation

- Just another kind of affixation, but here the morpheme goes inside a root

- Example from Tagalog:

- g<um>anda \(\rightarrow\) “become beautiful”

- h<um>irap \(\rightarrow\) “become difficult”

- … Where <um> is an infix whose meaning is “to become”.

Circumfixation

- Some languages may attach a prefix and and a suffix to a root. However, the prefix won’t attach to the root without the suffix, and vice versa.

- Tagalog: circumfixation of ka- and -an around a noun creates a noun meaning “a group of X” (sort of a collective noun)

- Intsik ‘Chinese person’ \(\rightarrow\) kaintsikan ‘the Chinese’

- pulo ‘island’ \(\rightarrow\) kapuluan ‘archipelago’

- Tagalog ‘Tagalog person’ \(\rightarrow\) katagalogan ‘the Tagalog’

Parasynthesis

This kind of affixation is a form of parasynthesis, a phenomenon in which a particular morphological category is signaled by the simultaneous presence of two morphemes.

Circumfixation

- However:

- Circumfixation is is not the only kind of parasynthesis!

- In any case, remember that for affixation to be a case of parasynthesis, you need to have both morphemes to make it work.

Stem change I: Ablaut and umlaut

- In some languages, the vowel in the root morpheme changes

\(\rightarrow\) Vowel /a/ for masculine, vowel /e/ for feminine

\(\rightarrow\) Vowel changes in terms of quality, quantity, and tone

\(\rightarrow\) Umlaut: A vowel changes its backness to (initially) match that of a suffix

Stem change II: Consonant mutations

- Some languages may change a consonant in the base, in terms of manner or articulation, place of articulation, voicing, or length.

\(\rightarrow\) No extra affix, only consonant change (what kind?)

\(\rightarrow\) Prefix and consonant change (what kind?)

Stem change III: Reduplication

- Some languages may repeat a part of a word in order to give that a different meaning

- These languages take a whole word and repeat it. This is called full reduplication. Note that the resulting meaning can be of different kinds: attenuative (Hausa), noun-forming (Samoan)…

Stem change III: Reduplication

- But full reduplication is not the only way to go:

\(\rightarrow\) The first syllable of the word is reduplicated

\(\rightarrow\) The first syllable of the word is reduplicated. If it’s a heavy syllable, it is repeated without change. If it’s a light syllable, it is made heavy by lengthening the vowel.

\(\rightarrow\) The last part of the word is repeated, in this case to convey a repetitive motion.

- What about English expressions such as fancy schmancy or mumbo jumbo?

Stem change IV: Templatic morphology

- A very well-known example of templatic morphology is Arabic:

- Consonants ktb \(\rightarrow\) ‘to write’.

- Active forms have /a/; passive forms have /u/ - /i/

- A triliteral root ( ktb ) provides the core meaning, and the vowels can go in different ways to convey further grammatical meaning, e.g. CVCVC (non-causative, non-reciprocal), CVCCVC (causative), CVVCVC (reciprocal), etc.

- These templates are called binyan.

Stem change V: Subtractive processes

- Instead of adding morphemes to a base, we can also remove bits:

- In Koasati, the plural is formed by subtracting the final vowel and consonant from the base

- What about hypocoristics in English?

Summary

- We have seen that the inventory of processes used by the languages of the world is huge!

- Some processes may be more frequent across languages than others

- Some of these lesser-known processes may be found even in English, though they are less productive and the conveyed meaning might be less easy to grasp

Next week

- Read Lieber, Ch. 4

- Attend the tutorial

- Ask away

English Morphology | Week 3: Lexeme formation II | Barrientos